by Adam Kazmi, Anthropology

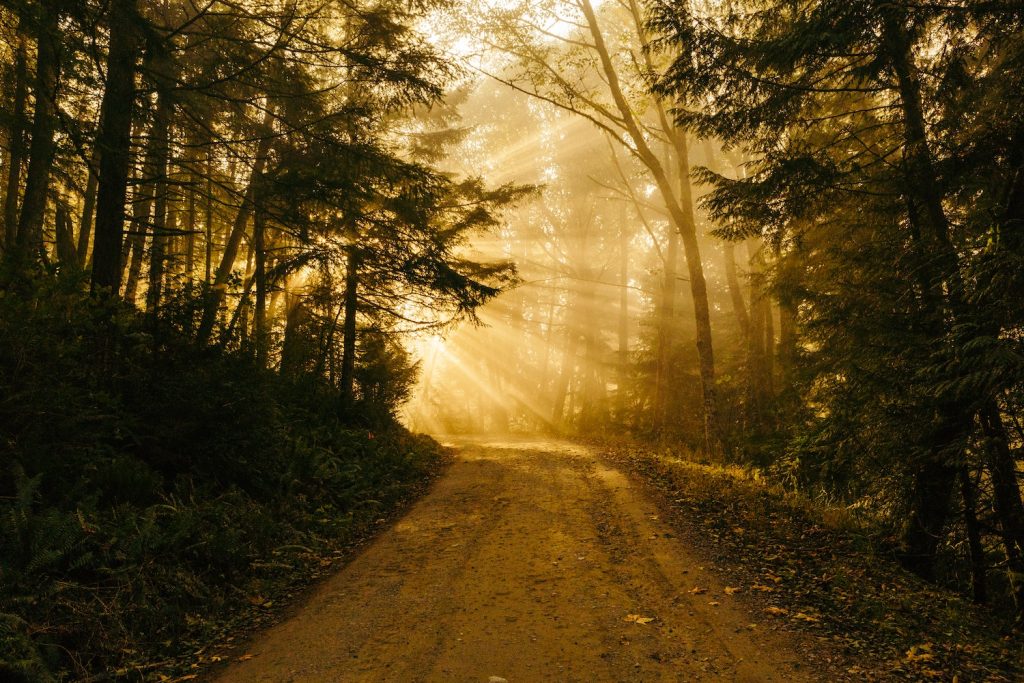

Why should we care about how well our undergraduate students can write, so long as they know the material? Ultimately, this question can be quite problematic for many teachers to answer, especially in fields that prioritize writing forms such as articles, reports, and memos. It is difficult enough for professors and graduate students to write their own publishable articles and essays, adding the task of teaching undergraduate students – who have different levels of motivation – how to write seems prohibitively difficult. But, in my own view, our goal as a writing coach is to encourage our students to develop their own ideas, styles, and voices. As such, it is not necessary to spend a great deal of time commenting on the technical errors, grammatical structures, or even issues with information. Our students most likely will not be publishing their ideas in scientific journals at the end of the course. At this stage of their career, students are developing their basic technical skills, including writing. We want to set our students down a path that will allow them to become better writers. We do not want to do the requisite work for them, which is what we would be doing if we colored an essay in red ink.

Realistically, most of our students will not remember specific course material five years from now. Instead, the impact of the course may be measured by the general skills and perspectives that were imparted through the lens of specific course content. My goal as a writing coach is to encourage students to transfer their thoughts and speech patterns into a comprehensible text that engages the reader intellectually while also remaining personable. The best writing almost always unfolds naturally, as a conversation would. Rather than trying to mimic the stale style of “objective” scientific articles derived largely from the positivist movement of the 50s on, it is possible to convey significant information without losing an “I.” This does not mean students should try their hardest to imbed layers of poetic genius and artistic flourish into their essays. Remaining down-to-earth and natural in our descriptions is a far more effective literary technique for communicating our most important meanings to the broadest audience possible. This approach to writing is extremely adaptable and may be used in professional, academic, and public settings.

Remaining down-to-earth and natural in our descriptions is a far more effective literary technique for communicating our most important meanings to the broadest audience possible.

Writing is by its very nature fluid. The intentions of the author and the context are all-important in determining the form of a work, which is why it can seem such an overwhelming task to teach someone how to write. Take a step back and remember the very basics and it will seem much clearer. All we really have to do is remind our students that they are their own people, with their own voices and opinions. Being a scientist does not entail losing that. If we mask our passion with too much uninvolved and disinterested language, soon that passion may too be gone, leaving only traces of meaning found among a litter of acronyms and jargon. Remind your students to remain true to their own passions and interests when they write, whatever the context may be.