by Jonathan Crum

In a 2018 overview of research on notetaking effectiveness, Kiewra et al. observe that students are, by and large, incomplete notetakers. Out of the content that students are expected to learn, approximately a third of it actually makes it into their notes (see Austen et al. 2004; Kiewra 2016; Titsworth 2004). As instructors, we strive to make our classes engaging and effective. It is dismaying, then, to learn that students are in the practice of crafting little effigies, to be burned as soon as created. That for all the work that goes into preparing material, students only actually walk away with a fraction of it.

There are two prongs to this—on the one hand, notetaking effectiveness impacts the instructional side as it casts light on areas where lessons can be tightened up, reorganized, or streamlined. On the other hand, notetaking effectiveness impacts the student, and not in the obvious way that they simply aren’t getting the material. More perniciously, the idea that notetaking is something that they should already be practiced in likely prevents outreach.

So what is to be done? Well, as the adage goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Before we can dive into the prevention, though, we should stop to consider what exactly the problem is, and ask where it goes awry.

In the conventional view, we can consider notetaking as being a process which leads to a concrete endpoint, the notes per se. In the processual mode, students come to class, listen to lecture or engage in activities, and record what they deem to be important details. Notetaking in this step has the effect of sharpening attention on the material at hand. Leaving class, students return home or, perhaps, to a study area and switch to notetaking in its product modality. Notes serve as materials to be observed and reviewed, often in preparation for homework or exams. In this mode, notes serve as mnemonic devices that frame the processing of content presented in class.

In general, the product component is the stronger of the two (cf. Kiewra et al. 1991; Kobayashi 2005; Rickards & Friedman 1978).

These two modalities of notetaking—process and product—raise at least two points where issues can arise, therefore where we can apply attention. Let us treat these as two issues in turn.

In the first case, relating to process, notes tend to be reactive or responsive to material in class, rather than proactive or anticipatory. When a student takes notes, they are attempting to represent the content of a lecture, but with this comes a dearth of context. There is also the base issue of speed. Wong (2014) clocks the average lecturer at a blinding 120 to 130 words per minute, while the average student recording by hand is lucky to eke out 25. Students reliant on technology fare little better, approaching 35 words per minute on average.

In the second case, relating to product, notes tend to be viewed as static objects. As the very name ‘product’ implies, they are the output of some activity. We can just as well take something produced and put it back into new processes, of course, but this is not the avenue students tend to travel. Notes end up being memetic rather than generative. They act as frameworks for filling in gaps, rather than being the engines of new ideas.

What we are left with is a chain of ever degrading representations that end in a compound mess.

Okay, so now that we have brought the problem into focus, how do we inoculate?

Returning to the study mentioned at the outset, Kiewra et al. (2018) offer a few useful suggestions.

One obvious possibility is to provide notes to students ourselves. This is a strategy that is used not infrequently in classrooms today, and for good reason. Kiewra and Benton (1987) performed an experiment where students were tasked with watching a 20 minute video lecture. One half of the students were permitted to take notes while the other half were told to simply watch the lecture. Afterwards, the notetaking half were permitted to use their own notes as study material, while the half that was instructed to abstain were given a set of complete notes by the instructor.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the students in the latter category scored 17% higher on average than those who took and reviewed their own notes.

But providing complete notes presents its own challenges. In the above study, the figure relied heavily on active participation by students in the first half of the experiment, attending to the lecture content regardless of experimental group. By providing complete notes, we may end up depriving students of the useful processual aspect of notetaking, and in the worst case promote inattention.

As it turns out, providing partial notes is demonstrably more effective. Instructors can provide incomplete but structured notes that act as a scaffold for in-class attention. This strategy is also in frequent use in the modern classroom, and again this is for very good reason. Kiewra et al. (1995) demonstrated that own-note students recorded approximately 38% of important lesson points. Students using a partial note scaffold, however, recorded closer to 60% of the material. I’ll certainly take a 200% increase, please and thanks!

Alongside these strategies, instructors can provide notetaking cues. We can typologize these into two categories, importance cues and organizational cues. The former signal students to attend to content more carefully, while the latter provide students some framing for what their notes should be used to accomplish. Locke (1977) demonstrated that these sorts of cues can push the figure of recorded content up to around 85%.

These are all good, and they smack of preventatives, but my suggestion is that these are still merely curative measures. Why? Although many of these strategies do teach students how to be effective notetakers, they still miss the bottom line.

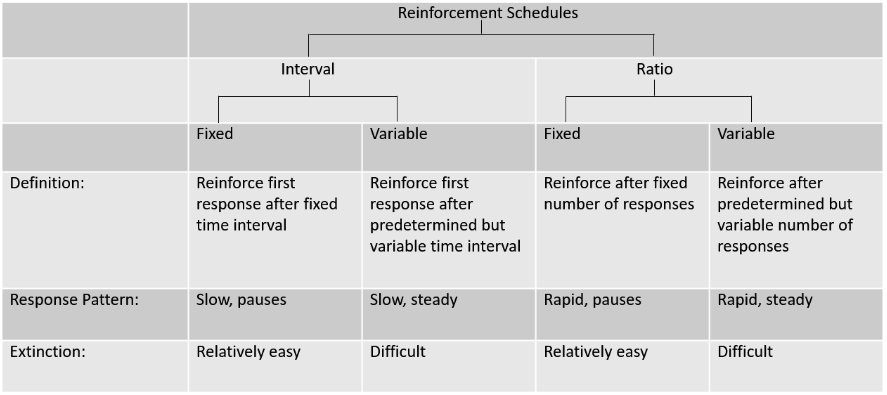

The role of notes is to be generative – to produce, not to record. And for that, we need to not just teach students how to take notes, but why to take them and how to use them effectively. Kiewra et al. provide one possible mechanism for achieving this, what they dub SOAR, for Select, Organize, Associate, and Regulate. The Select component gets checked off when students record complete notes. The Organize component is where instructors can step in by helping students to structure their notes at the outset. This can take the form of graphical organizers, structures, or concept matrices, as in the figure below.

The organization of concepts prepares students to move into the third component, Associate. With the information structured, new ideas can be drawn together, resulting in the generation of new avenues for investigation and learning. They can prime questions, promote retention for later recall, and generally ground the concepts in stronger mnemonic devices.

The final component, Regulation, involves the maintenance of learned material ahead of application. As with organization, this is an area where instructors can most effectively step in with the assist. In-class work, homework, and other tasks can be geared towards the regulation of content that has been carefully selected, diligently organized, and variously associated. Most importantly, this provides a natural framework for interleaving shared responsibilities among students and their peers, and students and instructors.

So take note, and be deliberate in the teaching of documentation practices.

References

Austin, J. L., Lee, M., & Carr, J. P. (2004). The effects of guided notes on undergraduates’ recording of lecture content. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31, 314–320.

Kiewra, K. A.. (2016). Note taking on trial: A legal application of note-taking research. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 377–384.

Kiewra, K. A., & Benton, S. L. (1987). Effects of notetaking, the instructor’s notes, and higher-order practice questions on factual and higher-order learning. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 14, 186–194.

Kiewra, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Christensen, M., Kim. S.-I., & Risch, N. (1991). Effects of repetition on recall and note-taking: Strategies for learning from lectures. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 83, 120–123.

Kiewra, K. A., Benton, S. L., Kim, S., Risch, N., & Christansen, M. (1995). Effects of note-taking format and study technique on recall and relational performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20, 172–187.

Kiewra, K. A., Colliot, T., & Lu, J. (2018). Note This: How to Improve Student Note Taking. IDEA Paper #73. IDEA Center, Inc.

Kobayashi, K. (2005). What limits the encoding effect of note-taking? A meta-analytic explanation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 242–262.

Locke, E. A. (1977). An empirical study of lecture note taking among college students. Journal of Educational Research, 77, 93-99.

Rickards, J. P., & Friedman, F. (1978). The encoding versus the external storage hypothesis in note taking. Reading World, 19(1), 51–56.

Titsworth, B. S. (2004). Students’ note taking: The effects of teacher immediacy and clarity. Communication Education, 53, 305–320.